Golang Datastructures: Trees

Table of Contents

You can spend quite a bit of your programming career without working with trees, or just by simply avoiding them if you don’t understand them (which is what I had been doing for a while).

Now, don’t get me wrong - arrays, lists, stacks and queues are quite powerful data structures and can take you pretty far, but there is a limit to their capabilities, how you can use them and how efficient that usage can be. When you throw in hash tables to that mix, you can solve quite some problems, but for many of the problems out there trees are a powerful (and maybe the only) tool if you have them under your belt.

So, let’s look at trees and then we can try to use them in a small exercise.

A touch of theory #

Arrays, lists, queues, stacks store data in a collection that has a start and an end, hence they are called “linear”. But when it comes to trees and graphs, things can get confusing since the data is not stored in a linear fashion.

Trees are called nonlinear data structures. In fact, you can also say that trees are hierarchical data structures since the data is stored in a hierarchical way.

For your reading pleasure, Wikipedia’s definition of trees:

A tree is a data structure made up of nodes or vertices and edges without having any cycle. The tree with no nodes is called the null or empty tree. A tree that is not empty consists of a root node and potentially many levels of additional nodes that form a hierarchy.

What the definition states are that a tree is just a combination of nodes (or vertices) and edges (or links between the nodes) without having a cycle.

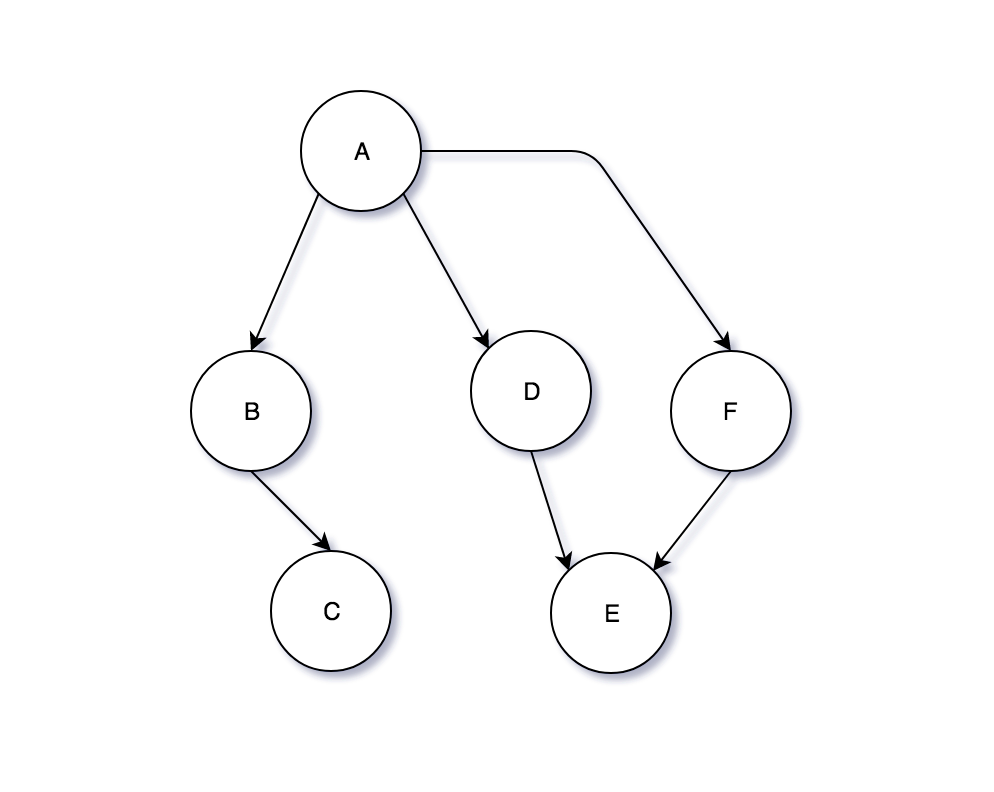

For example, the data structure represented on the diagram is a combination of nodes, named from A to F, with six edges. Although all of its elements look like they construct a tree, the nodes A, D, E and F have a cycle, therefore this structure is not a tree.

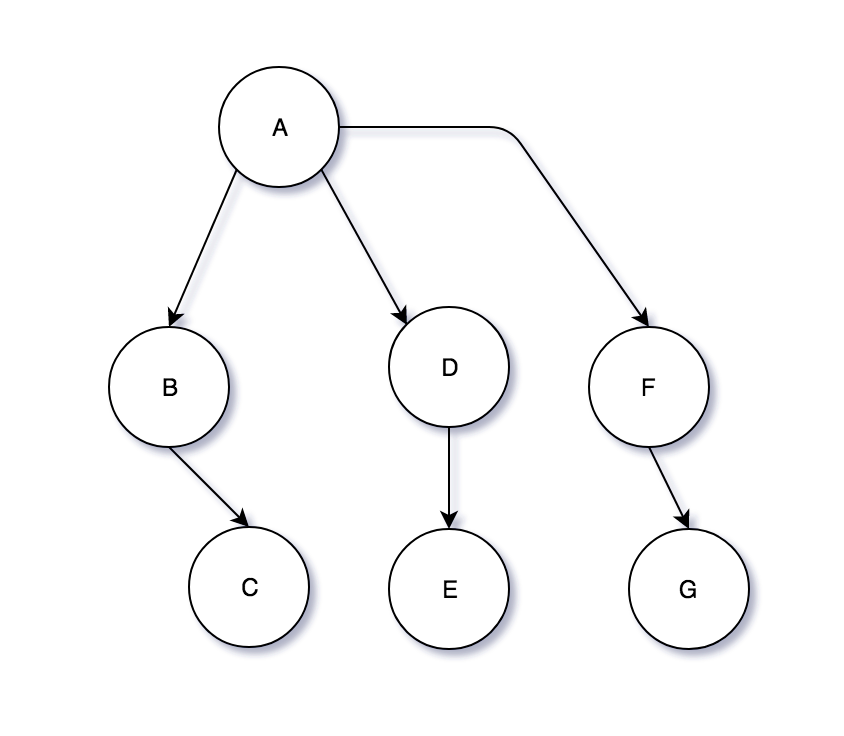

If we would break the edge between nodes F and E and add a new node called G with an edge between F and G, we would end up with something like this:

Now, since we eliminated the cycle in this graph, we can say that we have a valid tree. It has a root with the name A, with a total of 7 nodes. Node A has 3 children (B, D & F) and those have 3 children (C, E & G respectively). Therefore, node A has 6 descendants. Also, this tree has 3 leaf nodes (C, E & G) or nodes that have no children.

What do B, D & F have in common? They are siblings because they have the same parent (node A). They all reside on level 1 because to get from each of them to the root we need to take only one step. For example, node G has level 2, because the path from G to A is: G -> F -> A, hence we need to follow two edges to get to A.

Now that we know a bit of theory about trees, let’s see how we can solve some problems.

Modelling an HTML document #

If you are a software developer that has never written any HTML, I will just assume that you have seen (or have an idea) what HTML looks like. If you have not, then I encourage you to right click on the page that you are reading this and click on ‘View Source’.

Seriously, go for it, I’ll wait…

Browsers have this thing baked in, called the DOM - a cross-platform and language-independent application programming interface, which treats internet documents as a tree structure wherein each node is an object representing a part of the document. This means that when the browser reads your document’s HTML code it will load it and create a DOM out of it.

So, let’s imagine for a second we are developers working on a browser, like Chrome or Firefox and we need to model the DOM. Well, to make this exercise easier, let’s see a tiny HTML document:

<html>

<h1>Hello, World!</h1>

<p>This is a simple HTML document.</p>

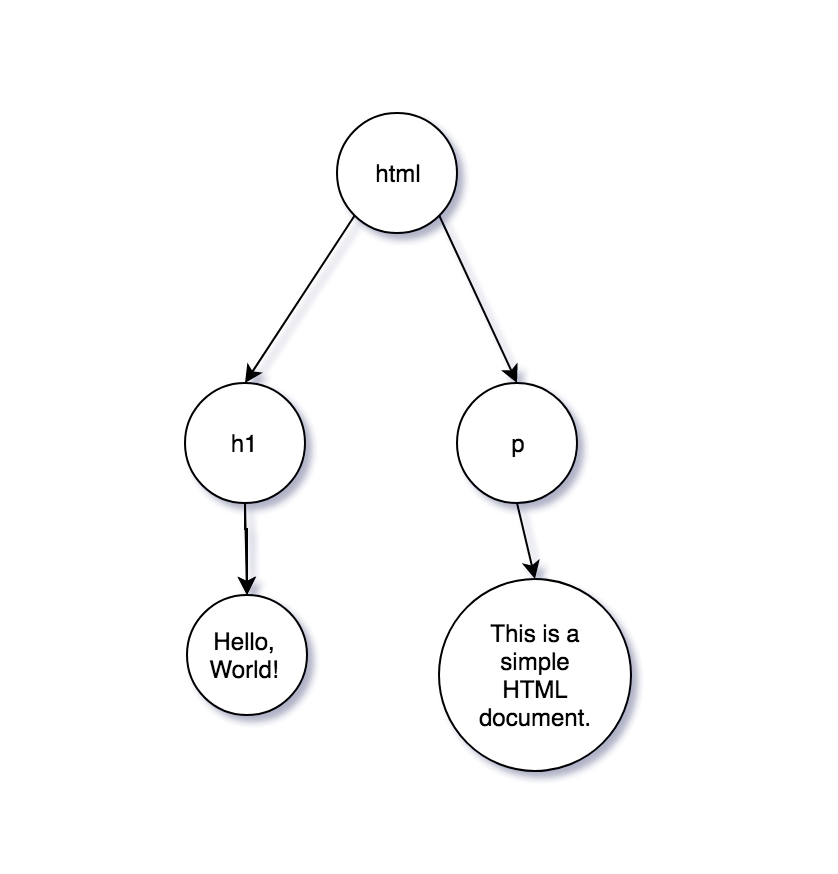

</html>So, if we would model this document as a tree, it would look something like this:

Now, we could treat the text nodes as separate Nodes, but we can make our

lives simpler by assuming that any HTML element can have text in it.

The html node will have two children, h1 and p, which will have tag,

text and children as fields. Let’s put this into code:

type Node struct {

tag string

text string

children []*Node

}A Node will have only the tag name and children optionally. Let’s try to

create the HTML document we saw above as a tree of Nodes by hand:

func main() {

p := Node{

tag: "p",

text: "This is a simple HTML document.",

id: "foo",

}

h1 := Node{

tag: "h1",

text: "Hello, World!",

}

html := Node{

tag: "html",

children: []*Node{&p, &h1},

}

}That looks okay, we have a basic tree up and running now.

Building MyDOM - a drop-in replacement for the DOM 😂 #

Now that we have some tree structure in place, let’s take a step back and see what kind of functionality would a DOM have. For example, if MyDOM (TM) would be a drop-in replacement of a real DOM, then with JavaScript we should be able to access nodes and modify them.

The simplest way to do this with JavaScript would be to use

document.getElementById('foo')This function would lookup in the document tree to find the node whose ID is

foo. Let’s update our Node struct to have more attributes and then work on

writing a lookup function for our tree:

type Node struct {

tag string

id string

class string

children []*Node

}Now, each of our Node structs will have a tag, children which is a slice

of pointers to the children of that Node, id which is the ID of that DOM

node and class which is the classes that can be applied to this DOM node.

Now, back to our getElementById lookup function. Let’s see how we could

implement it. First, let’s build an example tree that we can use for our lookup

algorithm:

<html>

<body>

<h1>This is a H1</h1>

<p>

And this is some text in a paragraph. And next to it there's an image.

<img src="http://example.com/logo.svg" alt="Example's Logo"/>

</p>

<div class='footer'>

This is the footer of the page.

<span id='copyright'>2019 © Ilija Eftimov</span>

</div>

</body>

</html>This is a quite complicated HTML document. Let’s sketch out its structure in Go

using the Node struct as a building block:

image := Node{

tag: "img",

src: "http://example.com/logo.svg",

alt: "Example's Logo",

}

p := Node{

tag: "p",

text: "And this is some text in a paragraph. And next to it there's an image.",

children: []*Node{&image},

}

span := Node{

tag: "span",

id: "copyright",

text: "2019 © Ilija Eftimov",

}

div := Node{

tag: "div",

class: "footer",

text: "This is the footer of the page.",

children: []*Node{&span},

}

h1 := Node{

tag: "h1",

text: "This is a H1",

}

body := Node{

tag: "body",

children: []*Node{&h1, &p, &div},

}

html := Node{

tag: "html",

children: []*Node{&body},

}We start building this tree bottom - up. That means we create structs from the

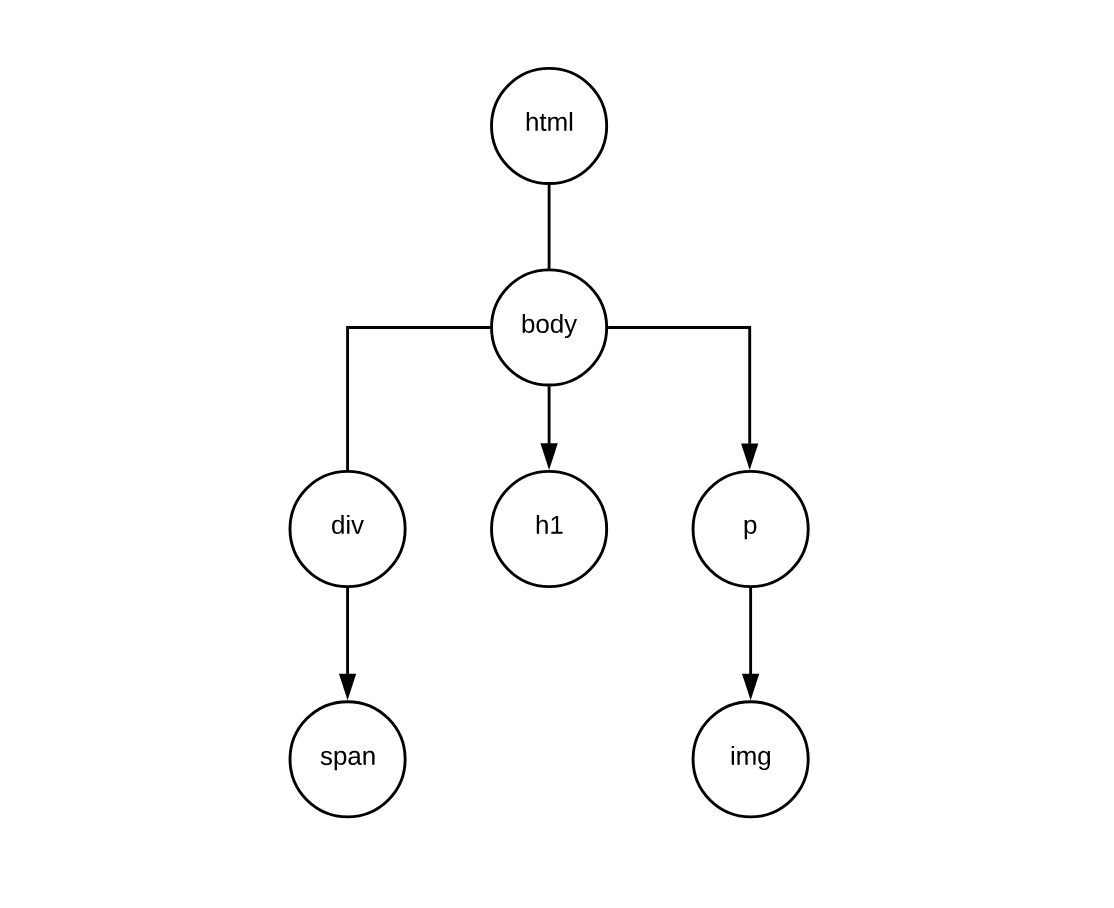

most deeply nested structs and working up towards body and html. Let’s look

at a graphic of our tree:

Implementing Node Lookup 🔎 #

So, let’s continue with what we were up to - allow JavaScript to call

getElementById on our document and find the Node that it’s looking for.

To do this, we have to implement a tree searching algorithm. The most popular approaches to searching (or traversal) of graphs and trees are Breadth First Search (BFS) and Depth First Search (DFS).

Breadth-first search ⬅➡ #

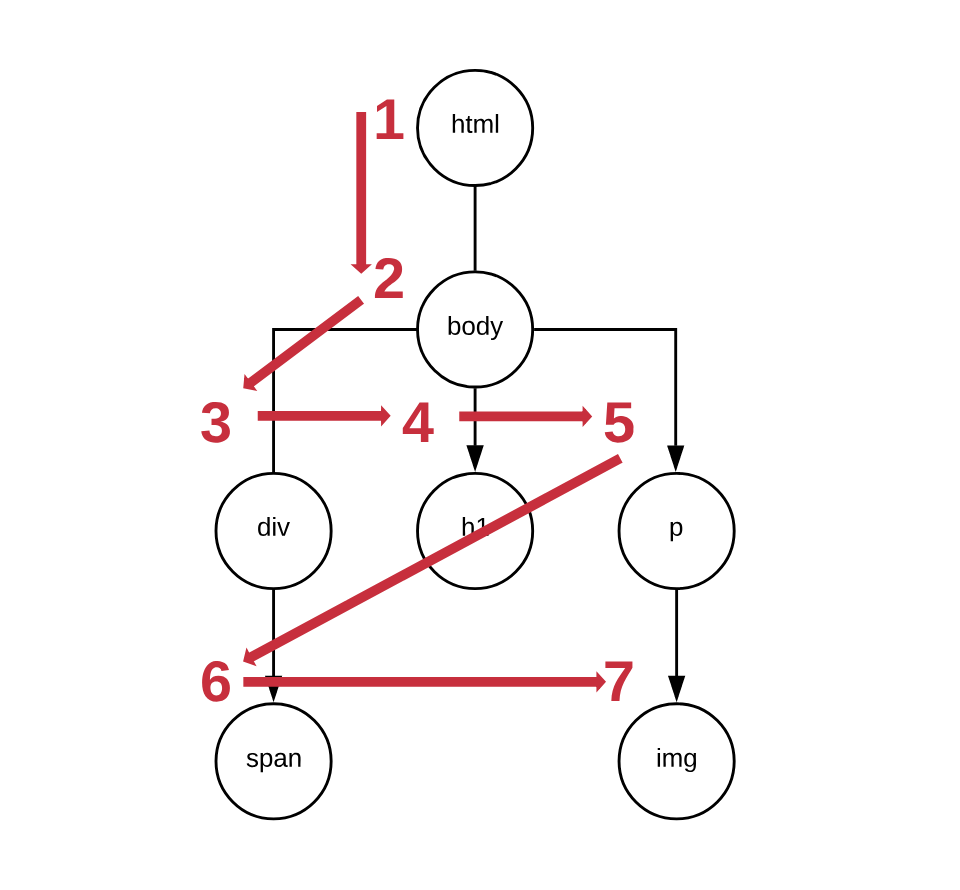

BFS, as its name suggests, takes an approach to traversal where it explores nodes in “width” first before it goes in “depth”. Here’s a visualisation of the steps a BFS algorithm would take to traverse the whole tree:

As you can see, the algorithm will take two steps in depth (over html and

body), but then it will visit all of the body’s children nodes before it

proceeds to explore in depth and visit the span and img nodes.

If you would like to have a step-by-step playbook, it would be:

- We start at the root, the

htmlnode - We push it on the

queue - We kick off a loop where we loop while the

queueis not empty - We check the next element in the

queuefor a match. If a match is found, we return the match and we’re done. - When a match is not found, we take all of the children of the node-under-inspection and we add them to the queue, so they can be inspected

GOTO4

Let’s see a simple implementation of the algorithm in Go and I’ll share some tips on how you can remember the algorithm easily.

func findById(root *Node, id string) *Node {

queue := make([]*Node, 0)

queue = append(queue, root)

for len(queue) > 0 {

nextUp := queue[0]

queue = queue[1:]

if nextUp.id == id {

return nextUp

}

if len(nextUp.children) > 0 {

for _, child := range nextUp.children {

queue = append(queue, child)

}

}

}

return nil

}The algorithm has three key points:

- The

queue- it will contain all of the nodes that the algorithm visits - Taking the first element of the

queue, checking it for a match, and proceeding with the next nodes if no match is found Queueing up all of the children nodes for a node before moving on in thequeue

Essentially, the whole algorithm revolves around pushing children nodes on a

queue and inspecting the nodes that are queued up. Of course, if a match is not

found at the end we return nil instead of a pointer to a Node.

Depth-first search ⬇ #

For completeness sake, let’s also see how DFS would work.

As we stated earlier, the depth-first search will go first in depth by visiting as many nodes as possible until it reaches a leaf. When then happens, it will backtrack and find another branch on the tree to drill down on.

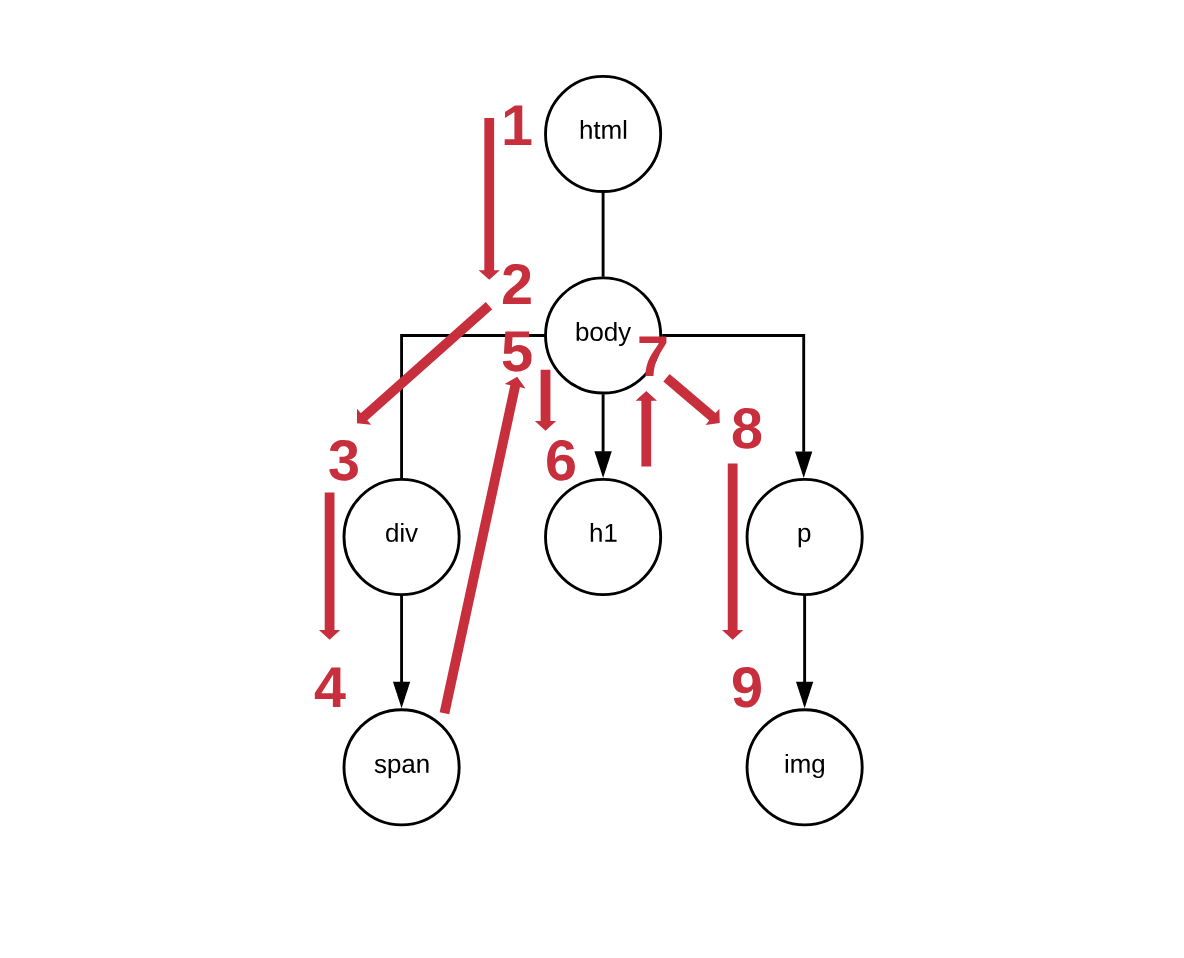

Let’s see what that means visually:

If this is confusing to you, worry not - I’ve added a bit more granularity in the steps to aid my explanation.

The algorithm starts off just like BFS - it walks down from html to body

and to div. Then, instead of continuing to h1, it takes another step to the

leaf span. Once it figures out that span is a leaf, it will move back up to

div to find other branches to explore. Since it won’t find any, it will move

back to body to find new branches proceeding to visit h1. Then, it will do

the same exercise again - go back to body and find that there’s another

branch to explore - ultimately visiting p and the img nodes.

If you’re wondering something along the lines of “how can we go back up to the parent without having a pointer to it”, then you’re forgetting one of the oldest tricks in the book - recursion. Let’s see a simple recursive Go implementation of the algorithm:

func findByIdDFS(node *Node, id string) *Node {

if node.id == id {

return node

}

if len(node.children) > 0 {

for _, child := range node.children {

findByIdDFS(child, id)

}

}

return nil

}

Finding by class name 🔎 #

Another functionality MyDOM (TM) should have is the ability to find

nodes by a class name. Essentially, when a JavaScript script executes

getElementsByClassName, MyDOM should know how to collect all nodes with a

certain class.

As you can imagine, this is also an algorithm that would have to explore the whole MyDOM (TM) tree and pick up the nodes that satisfy certain conditions.

To make our lives easier, let’s first implement a function that a Node can

receive, called hasClass:

func (n *Node) hasClass(className string) bool {

classes := strings.Fields(n.classes)

for _, class := range classes {

if class == className {

return true

}

}

return false

}hasClass takes a Node’s classes field, splits them on each space character

and then loops the slice of classes and tries to find the class name that we are

interested in. Let’s write a couple of tests that will test this function:

type testcase struct {

className string

node Node

expectedResult bool

}

func TestHasClass(t *testing.T) {

cases := []testcase{

testcase{

className: "foo",

node: Node{classes: "foo bar"},

expectedResult: true,

},

testcase{

className: "foo",

node: Node{classes: "bar baz qux"},

expectedResult: false,

},

testcase{

className: "bar",

node: Node{classes: ""},

expectedResult: false,

},

}

for _, case := range cases {

result := case.node.hasClass(test.className)

if result != case.expectedResult {

t.Error(

"For node", case.node,

"and class", case.className,

"expected", case.expectedResult,

"got", result,

)

}

}

}As you can see, the hasClass function will detect if a class name is in the

list of classes on a Node. Now, let’s move on to implementing MyDOM’s

implementation of finding all Nodes by class name:

func findAllByClassName(root *Node, className string) []*Node {

result := make([]*Node, 0)

queue := make([]*Node, 0)

queue = append(queue, root)

for len(queue) > 0 {

nextUp := queue[0]

queue = queue[1:]

if nextUp.hasClass(className) {

result = append(result, nextUp)

}

if len(nextUp.children) > 0 {

for _, child := range nextUp.children {

queue = append(queue, child)

}

}

}

return result

}If the algorithm seems familiar, that’s because you’re looking at a modified

findById function. findAllByClassName works just like findById, but

instead of returning the moment it finds a match, it will just append the

matched Node to the result slice. It will continue doing that until all of

the Nodes have been visited.

If there are no matches, the result slice will be empty. If there are any

matches, they will be returned as part of the result slice.

Last thing worth mentioning is that to traverse the tree we used a

Breadth-first approach here - the algorithm uses a queue for each of the

Nodes and loops over them while appending to the result slice if a match is

found.

Deleting nodes 🗑 #

Another functionality that is often used in the DOM is the ability to remove nodes. Just like the DOM can do it, also our MyDOM (TM) should be able to handle such operations.

The simplest way to do this operation in JavaScript is:

var el = document.getElementById('foo');

el.remove();While our document knows how to handle getElementById (by calling

findById under the hood), our Nodes do not know how to handle a remove

function. Removing a Node from the MyDOM (TM) tree would be a

two-step process:

- We have to look up to the

parentof theNodeand remove it from its parent’schildrencollection; - If the to-be-removed

Nodehas any children, we have to remove those from the DOM. This means we have to remove all pointers to each of the children and its parent (the node to-be-removed) so Go’s garbage collector can free up that memory.

And here’s a simple way to achieve that:

func (node *Node) remove() {

// Remove the node from it's parents children collection

for idx, sibling := range n.parent.children {

if sibling == node {

node.parent.children = append(

node.parent.children[:idx],

node.parent.children[idx+1:]...,

)

}

}

// If the node has any children, set their parent to nil and set the node's children collection to nil

if len(node.children) != 0 {

for _, child := range node.children {

child.parent = nil

}

node.children = nil

}

}A *Node would have a remove function, which does the two-step process of

the Node’s removal.

In the first step, we take the node out of the parent’s children list, by

looping over them and removing the node by appending the elements before the

node in the list, and the elements after the node.

In the second step, after checking for the presence of any children on the

node, we remove the reference to the parent from all the children and then we

set the Node’s children to nil.

Where to next? #

Obviously, our MyDOM (TM) implementation is never going to become a replacement for the DOM. But, I believe that it’s an interesting example that can help you learn and it’s pretty interesting problem to think about. We interact with browsers every day, so thinking how they could function under the hood is an interesting exercise.

If you would like to play with our tree structure and write more functionality, you can head over to WC3’s JavaScript HTML DOM Document documentation and think about adding more functionality to MyDOM.

Obviously, the idea behind this article was to learn more about trees (graphs) and learn about the popular searching/traversal algorithms that are used out there. But, by all means, please keep on exploring and experimenting and drop me a comment about what improvements you did to your MyDOM implementation.