Make resilient Go net/http servers using timeouts, deadlines and context cancellation

Table of Contents

When it comes to timeouts, there are two types of people: those who know how tricky they can be, and those who are yet to find out.

As tricky as they are, timeouts are a reality in the connected world we live in. As I am writing this, on the other side of the table, two persons are typing on their smartphones, probably chatting to people very far from them. All made possible because of networks.

Networks and all their intricacies are here to stay, and we, who write servers for the web, have to know how to use them efficiently and guard against their deficiencies.

Without further ado, let’s look at timeouts and how they affect our net/http

servers.

Server timeouts - first principles #

In web programming, the general classification of timeouts is client and server timeouts. What inspired me to dive into this topic was an interesting server timeout problem I found myself in. That’s why, in this article, we will focus on server-side timeouts.

To get the basic terminology out of the way: timeout is a time interval (or limit) in which a specific action must complete. If the operation does not complete in the given time limit, a timeout occurs, and the operation is canceled.

Initializing a net/http server in Golang reveals a few basic timeout

configurations:

srv := &http.Server{

ReadTimeout: 1 * time.Second,

WriteTimeout: 1 * time.Second,

IdleTimeout: 30 * time.Second,

ReadHeaderTimeout: 2 * time.Second,

TLSConfig: tlsConfig,

Handler: srvMux,

}This server of http.Server type can be initialized with four different

timeouts:

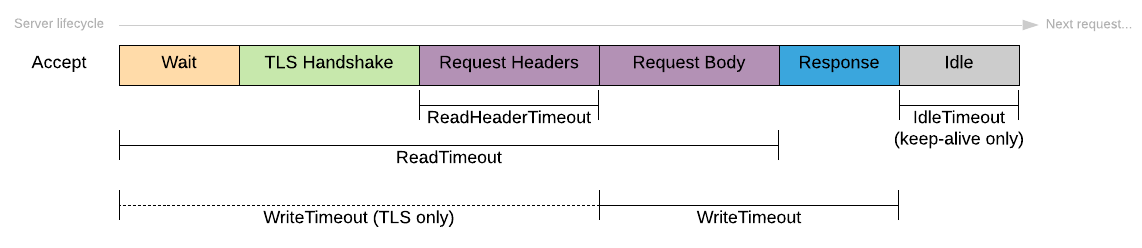

ReadTimeout: the maximum duration for reading the entire request, including the bodyWriteTimeout: the maximum duration before timing out writes of the responseIdleTimetout: the maximum amount of time to wait for the next request when keep-alive is enabledReadHeaderTimeout: the amount of time allowed to read request headers

A graphical representation of the above timeouts:

Before you start thinking that these are all the timeouts you need, tread carefully! There’s more than meets the eye here. These timeout values provide much more fine-grained control, and they are not going to help us to timeout our long-running HTTP handlers.

Let me explain.

Timeouts and deadlines #

If we look at the source of net/http, in particular, the conn

type,

we will notice that it uses net.Conn connection under the hood which

represents the underlying network connection:

// Taken from: https://github.com/golang/go/blob/bbbc658/src/net/http/server.go#L247

// A conn represents the server-side of an HTTP connection.

type conn struct {

// server is the server on which the connection arrived.

// Immutable; never nil.

server *Server

// * Snipped *

// rwc is the underlying network connection.

// This is never wrapped by other types and is the value given out

// to CloseNotifier callers. It is usually of type *net.TCPConn or

// *tls.Conn.

rwc net.Conn

// * Snipped *

}In other words, it’s the actual TCP connection that our HTTP

request travels on. From a type perspective, it’s a *net.TCPConn or

*tls.Conn if it’s a TLS connection.

The serve

function,

calls the readRequest function for each incoming

request.

readRequest uses the timeout

values

that we set on the server to set deadlines on the TCP connection:

// Taken from: https://github.com/golang/go/blob/bbbc658/src/net/http/server.go#L936

// Read next request from connection.

func (c *conn) readRequest(ctx context.Context) (w *response, err error) {

// *Snipped*

t0 := time.Now()

if d := c.server.readHeaderTimeout(); d != 0 {

hdrDeadline = t0.Add(d)

}

if d := c.server.ReadTimeout; d != 0 {

wholeReqDeadline = t0.Add(d)

}

c.rwc.SetReadDeadline(hdrDeadline)

if d := c.server.WriteTimeout; d != 0 {

defer func() {

c.rwc.SetWriteDeadline(time.Now().Add(d))

}()

}

// *Snipped*

}From the snippet above, we can conclude that the timeout values set on the server end up as TCP connection deadlines instead of HTTP timeouts.

So, what are deadlines then? How do they work? Will they timeout our connection if our request takes too long?

A simple way to think about deadlines is as a point in time at which restrictions on specific actions on the connection are enforced. For example, if we set a write deadline after the deadline time passes, any write actions on the connection will be forbidden.

While we can create timeout-like behavior using deadlines, we cannot control

the time it takes for our handlers to complete. Deadlines operate on the

connection, so our server will fail to return a result only after the handlers

try to access connection properties (such as writing to http.ResponseWriter).

To see this in action, let’s create a tiny handler that takes longer to complete relative to the timeouts we set on the server:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"io"

"net/http"

"time"

)

func slowHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, req *http.Request) {

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

io.WriteString(w, "I am slow!\n")

}

func main() {

srv := http.Server{

Addr: ":8888",

WriteTimeout: 1 * time.Second,

Handler: http.HandlerFunc(slowHandler),

}

if err := srv.ListenAndServe(); err != nil {

fmt.Printf("Server failed: %s\n", err)

}

}The server above has a single handler, which takes 2 seconds to complete. On the

other hand, the http.Server has a WriteTimeout set to 1 second. Due to the

configuration of the server, we expect the handler to be unable to write the

response to the connection.

We can start the server using go run server.go. To send a request we can

curl localhost:8888:

$ time curl localhost:8888

curl: (52) Empty reply from server

curl localhost:8888 0.01s user 0.01s system 0% cpu 2.021 totalThe request took 2 seconds to complete, and the response from the server was empty. While our server knows that we cannot write to our response after 1 second, the handler still took 100% more (2 seconds) to complete.

While this is a timeout-like behavior, it would be more useful to stop our server from further execution when it reaches the timeout, ending the request. In our example above, the handler proceeds to process the request until it completes, although it takes 100% longer (2 seconds) than the response write timeout time (1 second).

The natural question is, how can we have efficient timeouts for our handlers?

Handler timeout #

Our goal is to make sure our slowHandler does not take longer than 1 seconds

to complete. If it does take longer, our server should stop its execution and

return a proper timeout error.

In Go, as with other programming languages, composition is very often the

favored approach to writing and designing code. The net/http

package of the standard library is one of the

places where having compatible components that one can put together with little

effort is an obvious design choice.

In that light, the net/http packages provide a

TimeoutHandler - it returns

a handler that runs a handler within the given time limit.

Its signature is:

func TimeoutHandler(h Handler, dt time.Duration, msg string) HandlerIt takes a Handler as the first argument, a time.Duration as the second

argument (the timeout time) and a string, the message returned when it hits

the timeout.

To wrap our slowHandler within a TimeoutHandler, all we have to do is:

package main

import (

"fmt"

"io"

"net/http"

"time"

)

func slowHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, req *http.Request) {

time.Sleep(2 * time.Second)

io.WriteString(w, "I am slow!\n")

}

func main() {

srv := http.Server{

Addr: ":8888",

WriteTimeout: 5 * time.Second,

Handler: http.TimeoutHandler(http.HandlerFunc(slowHandler), 1*time.Second, "Timeout!\n"),

}

if err := srv.ListenAndServe(); err != nil {

fmt.Printf("Server failed: %s\n", err)

}

}The two notable changes are:

- We wrap our

slowHanlderin thehttp.TimetoutHandler, setting the timeout to 1 second and the timeout message to “Timeout!”. - We increase the

WriteTimeoutto 5 seconds, to give thehttp.TimeoutHandlertime to kick in. If we don’t do this when theTimeoutHandlerkicks in, the deadline will pass, and it won’t be able to write to the response.

If we started the server again and hit the slow handler we’ll get the following output:

$ time curl localhost:8888

Timeout!

curl localhost:8888 0.01s user 0.01s system 1% cpu 1.023 totalAfter a second, our TimeoutHandler will kick in, stop processing the

slowHandler, and return a plain “Timeout!” message. If the message we set

is blank, then the handler will return the default timeout response, which is:

<html>

<head>

<title>Timeout</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>Timeout</h1>

</body>

</html>Regardless of the output, this is pretty neat, isn’t it? Our application now is protected from long-running handlers and specially crafted requests made to cause very long-running handlers, leading to a potential DoS (Denial of Service) attack.

It’s worth noting that although setting timeouts is a great start, it’s still elementary protection. If you’re under threat of an imminent DoS attack, you should look into more advanced protection tools and techniques. (Cloudflare is a good start.)

Our slowHandler is a simple example-only handler. But, what if our

application was much more complicated, making external calls to other services

or resources? What if we had an outgoing request to a service such as S3 when

our handler would time out?

What would happen then?

Unhandled timeouts and request cancellations #

Let’s expand our example a bit:

func slowAPICall() string {

d := rand.Intn(5)

select {

case <-time.After(time.Duration(d) * time.Second):

log.Printf("Slow API call done after %s seconds.\n", d)

return "foobar"

}

}

func slowHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

result := slowAPICall()

io.WriteString(w, result+"\n")

}Let’s imagine that initially we didn’t know that our slowHandler took so long

to complete because it was sending a request to an API - using the

slowAPICall function.

The slowAPICall function is straightforward: using select and a

time.After it blocks between 0 and 5 seconds. Once that period passes, the

time.After method sends a value through its channel and "foobar" will be

returned.

(An alternative approach is to use sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(5)) * time.Second), but we will stick to select because it will make our life

simpler in the next example.)

If we run our server, we would expect the timeout handler to cut off the request processing after 1 second. Sending a request proves that:

$ time curl localhost:8888

Timeout!

curl localhost:8888 0.01s user 0.01s system 1% cpu 1.021 totalBy looking at the server output, we will notice that it prints the loglines after a few seconds instead of when the timeout handler kicks in:

$ go run server.go

2019/12/29 17:20:03 Slow API call done after 4 seconds.Such behavior suggests that although the request timed out after 1 second, the server proceeded to process the request fully. That’s why it printed the logline after 4 seconds passed.

While this example is trivial and naive, such behavior in production servers

can become a rather big problem. For example, imagine if the slowAPICall

function spawned hundreds of goroutines, each of them processing some data. Or

if it was issuing multiple API calls to various systems. Such long-running

processes will eat up resources from your system, while the caller/client won’t

ever use their result.

So, how can we guard our system from such unoptimized timeouts or request cancellations?

Context timeouts and cancellation #

Go comes with a neat package for handling such scenarios called

context.

The context package was promoted to the standard library as of Go 1.7.

Previously it was part of the Go Sub-repository

Packages, with the name

golang.org/x/net/context

The package defines the Context type. It’s primary purpose is to carry

deadlines, cancellation signals, and other request-scoped values across API

boundaries and between processes. If you would like to learn more about the

context package, I recommend reading “Go Concurrency Patterns: Context” on

Golang’s blog.

The Request type that is part of the net/http package already has a

context attached to it. As of Go 1.7, Request has a Context

function, which returns the

request’s context. For incoming server requests, the server cancels the context

when the client’s connection closes, when the request is canceled (in HTTP/2),

or when the ServeHTTP method returns.

The behavior we are looking for is to stop all further processing on the

server-side when the client cancels the request (we hit CTRL + C on our

cURL) or the TimeoutHandler steps in after some time and ends the request.

That will effectively close all connections and free all other resources taken

up by the running handler (and all of its children goroutines).

Let’s use the request Context to pass it to the slowAPICall function as

an argument:

func slowAPICall(ctx context.Context) string {

d := rand.Intn(5)

select {

case <-time.After(time.Duration(d) * time.Second):

log.Printf("Slow API call done after %d seconds.\n", d)

return "foobar"

}

}

func slowHandler(w http.ResponseWriter, r *http.Request) {

result := slowAPICall(r.Context())

io.WriteString(w, result+"\n")

}Now that we utilize the request context, how can we put it in action? The

Context type has a Done

attribute, which is of type <-chan struct{}. Done closes when the work

done on behalf of the context should be canceled, which is what we need in the

example.

Let’s handle the ctx.Done channel in the select block in the slowAPICall

function. When we receive an empty struct via the Done channel, this

signifies the context cancellation, and we have to return a zero-value string

from the slowAPICall function:

func slowAPICall(ctx context.Context) string {

d := rand.Intn(5)

select {

case <-ctx.Done():

log.Printf("slowAPICall was supposed to take %s seconds, but was canceled.", d)

return ""

case <-time.After(time.Duration(d) * time.Second):

log.Printf("Slow API call done after %d seconds.\n", d)

return "foobar"

}

}(This is the reason we used a select block, instead of the time.Sleep - we

can just handle the Done channel in the select here.)

In our limited example, this does the trick – when we receive value through the

Done channel, we log a line to STDOUT and return an empty string. In more

complicated situations, such as sending real API requests, you might need to

close down connections or clean up file descriptors.

Let’s spin up the server again and send a cURL request:

# The cURL command:

$ curl localhost:8888

Timeout!

# The server output:

$ go run server.go

2019/12/30 00:07:15 slowAPICall was supposed to take 2 seconds, but was canceled.So check this out: we ran a cURL to the server, it took longer than 1 second,

and our server canceled the slowAPICall function. And we didn’t need to write

almost any code for it. The TimeoutHandler did this for us - when the handler

took longer than expected, the TimeoutHandler stopped the execution of the

handler and canceled the request context.

The TimeoutHandler performs the context cancellation in the

timeoutHandler.ServeHTTP

method:

// Taken from: https://github.com/golang/go/blob/bbbc658/src/net/http/server.go#L3217-L3263

func (h *timeoutHandler) ServeHTTP(w ResponseWriter, r *Request) {

ctx := h.testContext

if ctx == nil {

var cancelCtx context.CancelFunc

ctx, cancelCtx = context.WithTimeout(r.Context(), h.dt)

defer cancelCtx()

}

r = r.WithContext(ctx)

// *Snipped*

}Above, we use the request context by invoking context.WithTimeout on it. The

timeout value h.dt, which is the second argument received by the

TimeoutHandler, is applied to the context. The returned context is a copy of

the request context with a timeout attached. Right after, it’s set as the

request’s context using the r.WithContext(ctx) invocation.

The context.WithTimeout function makes the context cancellation. It returns a

copy of the Context with a timeout set to the duration passed as an argument.

Once it reaches the timeout, it cancels the context.

Here’s the code that does it:

// Taken from: https://github.com/golang/go/blob/bbbc6589/src/context/context.go#L486-L498

func WithTimeout(parent Context, timeout time.Duration) (Context, CancelFunc) {

return WithDeadline(parent, time.Now().Add(timeout))

}

// Taken from: https://github.com/golang/go/blob/bbbc6589/src/context/context.go#L418-L450

func WithDeadline(parent Context, d time.Time) (Context, CancelFunc) {

// *Snipped*

c := &timerCtx{

cancelCtx: newCancelCtx(parent),

deadline: d,

}

// *Snipped*

if c.err == nil {

c.timer = time.AfterFunc(dur, func() {

c.cancel(true, DeadlineExceeded)

})

}

return c, func() { c.cancel(true, Canceled) }

}Here we meet deadlines again. The WithDeadline function sets a function that

executes after the duration d passes. Once the duration passes, it invokes

the cancel method on the context, which will close the done channel of the

context and will set the context’s timer attribute to nil.

The closing of the Done channel effectively cancels the context, which allows

our slowAPICall function to stop its execution. That’s how the

TimeoutHandler timeouts long-running handlers.

(If you would like to read the code that does the above, you should see the

cancel functions on the cancelCtx

type

and the timerCtx

type.)

Resilient net/http servers #

Connection deadlines provide low-level fine-grained control. While their names contain “timeout” they do not have the behavior that folks commonly expect from timeouts. They are in fact very powerful, but they expect the programmer to know how to wield that weapon.

On the other hand, when working with HTTP handlers, the TimeoutHandler should

be our go-to tool. The design chosen by the Go authors, of having composable

handlers, provides flexibility, so much that we could even have different

timeouts per handler if we decided to. TimeoutHandler provides execution

control while maintaining the behavior that we commonly expect when thinking of

timeouts.

On top of that, the TimeoutHandler works well with the context package.

While the context package is simple, it carries cancellation signals and

request-scoped data, that we can use to make our applications adhere better to

the intricacies of networks.

Before we close, here are three suggestions on how to think of timeouts while writing your HTTP servers:

- Most-often, reach for

TimeoutHandler. It does what we commonly expect of timeouts. - Never forget context cancellations. The

contextpackage is simple to use and can save your servers lots of processing resources. Especially againts bad actors or misbehaving networks. - By all means, use deadlines. Just make sure you test thoroughly that they provide you the functionality that you want.

To read more on the topic:

- “The complete guide to Go net/http timeouts” on Cloudflare’s blog

- “So you want to expose Go on the Internet” on Cloudflare’s blog

- “Use http.TimeoutHandler or ReadTimeout/WriteTimeout?” on Stackoverflow

- “Standard net/http config will break your production environment” on Simon Frey’s blog