The practicality of designing and describing your APIs

Table of Contents

The web, as we all know, is driven by APIs. Since the rise of mobile applications and the JavaScript driven single-page applications, APIs became even more popular, as a unified way for the clients to communicate with the back-end. Most of the companies use internal APIs for different purposes. Some use them to expose resources, data or behaviour. Others, use them for authentication and authorisation, some do it for controlling the hardware layer with smart implementations under the hood. Overall, APIs are enablers that allow various clients to utilise the same back-end logic.

As we all know, banging some endpoints out of your head on the fly is rather easy. Maybe that approach will cut it for your internal API. Most probably not, but you could find your way around it. But, what if you wanted to expose a public API for your product, just like Facebook, Twitter, GitHub and a load of other companies do?

The design process #

APIs need consistent and stable design. That means that, once an API is released and clients start using it, breaking changes are a no-go. Even if you want to provide backwards compatibility for (otherwise a breaking) change, it will be a big hassle to pull off.

That means when building APIs we need to think about proper design. Yes, way before we put any code in, we have to think about various things. I am sure some of you find this obvious, but is it that obvious? And even then, how can we actually do it?

An API design means that we need to take various steps to achieve a well though out design before we have any code in place. We need to think about versioning, headers, response format, caching. We need to think about filtering, sorting and pagination of resources. Returning useful meta information, using appropriate HTTP verbs, security, authentication and what not. Since an API has so many moving parts, just putting some endpoints in place without putting (a lot of) thought into them will not do the trick.

Oh, and what about REST?

Thinking about REST #

REST as a concept is a really neat way to represent state and resources, while having a very intuitive design. REST means that your API has to be separated in logical resources. These resources then can be manipulated via HTTP requests, by using the appropriate methods. You know, whether a request uses the GET or the POST HTTP method has a big difference, for a good reason.

All of these things put together mean that designing an API has to be taken very seriously and writing documentation and/or blueprints is a very nice step towards a great API design.

Writing a blueprint #

If you got so far, I assume that you agree with my point. So, how can we improve our workflow?

Well, although I often get the “hack-n-slash” urge, I believe that APIs have to be done with a design-first approach. You can compare it to tests in test-driven development.

Every API has to have a contract before it is developed. This is where tools like API blueprint come in handy. API Blueprint is a way (or syntax) to define and design APIs in a standardised manner. This means that by writing a special flavour of markdown, a team (or teams) of developers can collaborate to design APIs to the best of their knowledge.

Blueprints allow developers to define metadata, resource groups, resources, actions and so on. You can define requests and responses in various formats (like XML and JSON), specify request and response headers.

Let’s see an small example of an API blueprint.

FORMAT: 1A

HOST: https://polls.apiblueprint.org/

# Polls

Polls is a simple web service that allows consumers to view polls and vote in them.

# Polls API Root [/]

This resource does not have any attributes. Instead it offers the initial API affordances in the form of links in the JSON body.

It is recommended to follow the “url” link values or Link headers to get to resources instead of constructing your own URLs to keep your client decoupled from implementation details.

## Retrieve the Entry Point [GET]

+ Response 200 (application/json)

{

"questions_url": "/questions"

}

## Group Question

Resource related to questions in the API.

## Question [/questions/{question_id}]

A Question object has the following attributes.

- question

- published_at

- url

- choices (an array of Choice objects).

+ Parameters

+ question_id (required, number, `1`) ... ID of the Question in form of an integer

### View a question detail [GET]

+ Response 200 (application/json)

{

"question": "Favourite programming language?",

"published_at": "2014-11-11T08:40:51.620Z",

"url": "/questions/1",

"choices": [

{

"choice": "Swift",

"url": "/questions/1/choices/1",

"votes": 2048

}, {

"choice": "Python",

"url": "/questions/1/choices/2",

"votes": 1024

}, {

"choice": "Objective-C",

"url": "/questions/1/choices/3",

"votes": 512

}, {

"choice": "Ruby",

"url": "/questions/1/choices/4",

"votes": 256

}

]

}As you can notice, the API blueprint starts with the format and the host where

the API is located. Then, it describes resource groups, like Polls, and

endpoints like Polls API Root [/]. Then, every endpoint is described by

providing the appropriate HTTP verb, with the description and the request and

response body.

Where’s the value? #

By having a blueprint of an endpoint, we create a contract to which our API has to oblige. This is very useful, since we provide ground rules and high-level overview of our API, but still we have technical and design decisions easily visible.

Think about this case - there’s an API that for some endpoints has to provide

metadata. Great, nothing out of the ordinary. A valid question is, what will

the metadata look like? Usually, metadata contains a cursor, or in other words,

pagination data like page, per_page, or limit and offset. Almost always

it contains the total number of objects that the API contains of the

requested resource. Often, it contains the attribute that we order by and the

ordering direction. In JSON, that would looks something like this:

{

"meta": {

"limit": 10,

"offset": 20,

"order_by": "id",

"order_dir": "desc",

"total": 200

}

}But, will this be useful? Sure it will, but are we missing any data here? Maybe you would like to provide the locale as part of the metadata? By leaving these questions unanswered, you are immediately adding “design debt” to your API. This means that, if a client needs the locale, you will have to change the contract of the API itself, for all endpoints.

By taking a step back while designing the API, we can describe our metadata in a blueprint. This allows us to see in advance how our API responses will look like and we can have a meaningful discussion with our colleagues about it. That is why, these sort of decisions have to be documented. Imagine changing the metadata structure on a live API, for example, removing or changing the name of an attribute of the metadata - most (if not all) clients that use it will break.

Exploring an API #

Another very important side-effect of using an API blueprint is explorability. To discover an API means that you can test and use the endpoints via a tool or your browser. It means that the consumer can see the data coming in and out of the API.

To do this, the consumer will have to know the location, the endpoints, the data format, parameters, headers and whatnot. Simply said, the consumer needs a detailed API documentation.

Resources #

Even if we have our endpoints thought out, we have to remember that if we are building a REST API we need to think about resources. “Sure”, you might think, “we will replicate the database model in our API”. Are you sure you want and (more importantly) need this?

Although REST APIs expose resources, APIs also expose behaviour. You have to ask yourself “what behaviour I want to give to the consumers” and “what are the resources that this behaviour will expose”. To do this, API blueprint has a very neat tool called MSON. MSON is an acronym for “Markdown Syntax for Object Notation” and it is a way to represent data structures in markdown.

While we describe our API endpoints in a blueprint, we also need to describe

the data objects that will be returned. For example, if we have a Product

object we can describe it as follows:

# Product

A product from Acme's catalog

## Properties

- id: 1 (number, required) - The unique identifier for a product

- name: A green door (string, required) - Name of the product

- price: 12.50 (number, required)

- tags: home, green (array[string])As you can see, it is quite trivial to write and to read. A Product has a

description and properties. The properties is a list of items, with a name,

type, presence and a description. By looking at this MSON file, we can see that

our JSON representation of this object will look like:

{

"id": 1,

"name": "A green door",

"price": 12.50,

"tags": [ "home", "green" ]

}By knowing what our endpoints return and what these objects look, we can easily explore our API. There is less friction and no “guess work” - you just know what to call and what the call will return.

If you would like to read more about MSON, I recommend checking their short tutorial. It demostrates more cool features, like inheritance, nesting and so on.

Everyday exploring #

This is what an API blueprint can provide. You can take your API blueprint file and convert it to a Postman collection. You can in fact use the awesome API Transformer tool and convert it to any format you want.

For example, let’s imagine we have the following API Blueprint ready for one of our APIs:

FORMAT: 1A

HOST: http://coconut-api.apiblueprint.org/

# Coconut API

API for all Coconut actions

## Account [/api/v1/accounts/{account_id}]

Exposes the `Account` resource.

### Fetch Account [GET]

Fetch Account data

+ Parameters

+ account_id (number) - ID of the Account in the form of an integer

+ Response 200 (application/json)

{

"id": 123,

"first_name": "Ilija",

"last_name": "Eftimov",

"email": "[email protected]",

"uuid": 0beec7b5ea3f0fdbc95d0dd47f3c5bc275da8a33

}The output of the API Transformer can be a Swagger JSON file:

{

"swagger": "2.0",

"info": {

"version": "",

"title": "Coconut API",

"description": "TODO: Add a description",

"license": {

"name": "MIT",

"url": "http://github.com/gruntjs/grunt/blob/master/LICENSE-MIT"

}

},

"host": "coconut-api.apiblueprint.org",

"basePath": "/",

"securityDefinitions": {},

"schemes": [

"http"

],

"consumes": [

"application/json"

],

"produces": [

"application/json"

],

"paths": {

"/api/v1/accounts/{account_id}": {

"get": {

"description": "Fetch Account data",

"operationId": "Fetch Account_",

"produces": [

"application/json"

],

"parameters": [

{

"name": "account_id",

"in": "path",

"required": true,

"x-is-map": false,

"type": "number",

"format": "double",

"description": "ID of the Account in the form of an integer"

}

],

"responses": {

"200": {

"description": "",

"schema": {

"type": "object"

}

}

}

}

}

}

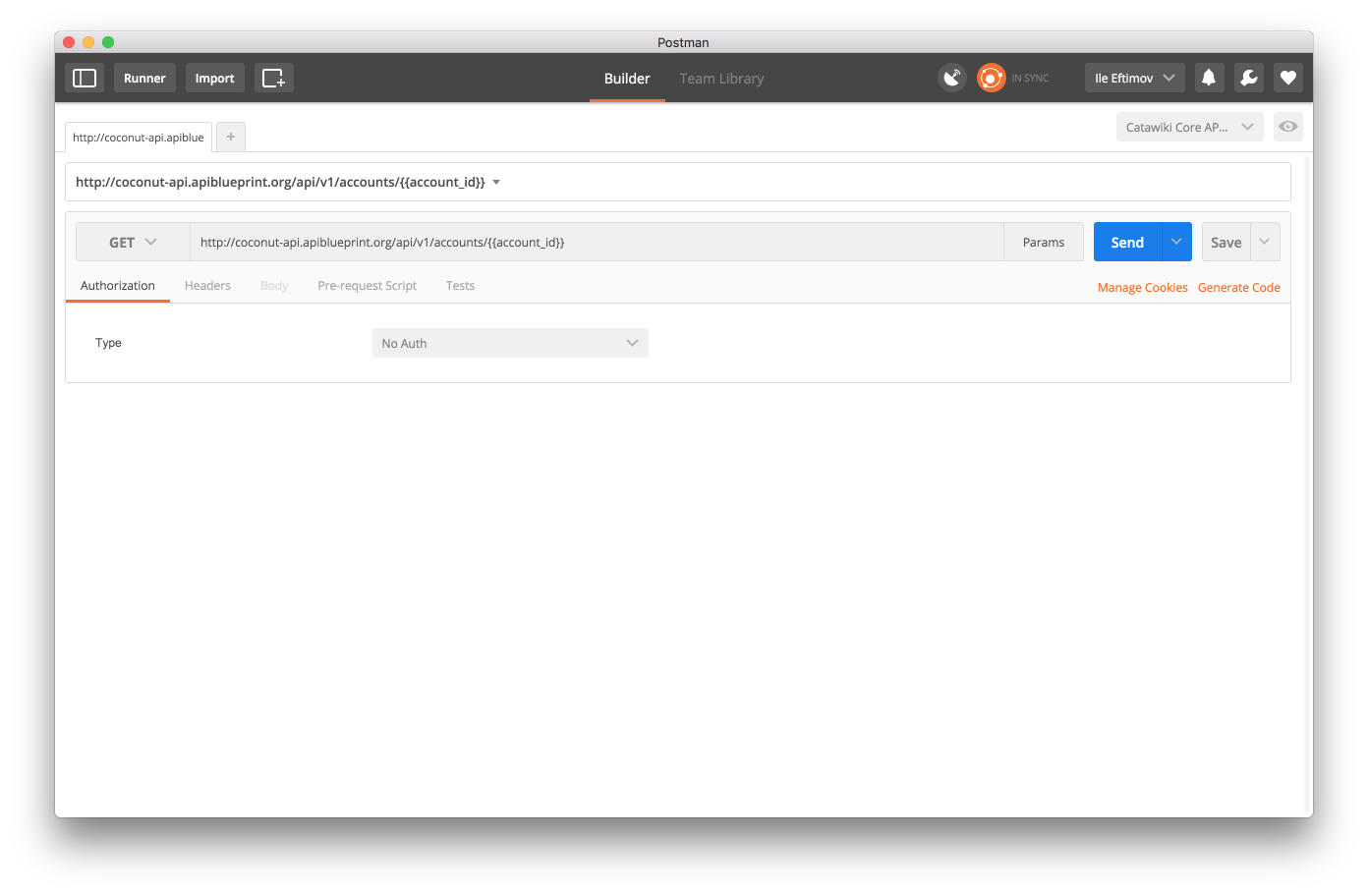

}Since Postman has the ability to import Swagger JSON, you can get the actual endpoint in your Postman and you can immediately fire requests away. Here is how my actual Postman looks like after importing the JSON above:

Additionally, you can use full blown explorers like Apiary that will put your blueprint on steroids. It will provide various examples on how to send requests to the API, with a mock server, live editor and documentation style page. You can see the API blueprint from above on Apiary here.

Last but very important, you can use tools like swagger-codegen to dynamically generate an API client by feeding it your Swagger Resource Declaration (the JSON file from above).

You can see all of the tools that API Blueprint has currently available and how you can fit it into your workflow.

Outro #

As you can see, there are plenty of design questions that we as developers have to answer. Sure, we take pride and have passion for what we do, but often we resort to hacking some endpoints before thinking about them. But if we document and design our APIs before we start building them, we will sleep better knowing that our clients will function well. And as enablers, a non-functioning client means a broken API. Or a broken design.

Also, the vast choice of tools that work with API Blueprints can completely change the way you build your APIs (and their clients). You can even generate real code out of the API Blueprint, by converting it to Swagger JSON first. All of this seems unreal, but once you get it in your workflow you can immediately feel the benefits. I mean, who doesn’t like documentations on steroids, request examples, mock servers for free, automatic generation of API clients and so on?

Or, you can just bang out those couple of endpoints you need. The choice is yours.

Acknowledgements: [Fotos Georgiadis](https://twitter.com/gfotos) made substantial comments on the drafts of this post. He also corrected some minor typos and proposed better or more explicit wording for some of it's segments.