Sprinkle some HATEOAS on your Rails APIs

Table of Contents

REST as a concept was introduced by Roy Fielding in his doctoral thesis, named Architectural Styles and the Design of Network-based Software Architectures. 16 years later, REST as an architecture is the most widely accepted way to design and build APIs. I am sure we have all heard about it, and most of us think we are building actual RESTful APIs. But, are we?

Let’s remind ourselves what REST is and then continue on something else that supplements REST, called HATEOAS.

So, what was REST again? #

I was thinking of a good way to explain this, but this gem by Ryan Tomako named How I Explained REST to My Wife is the best explanation of REST I have seen so far.

Overall, REST (an acronym for REpresentational State Transfer) is an architecture over which the Internet is built upon. The easiest way to explain REST is, in my opinion, the Richardson Maturity Model. Here, we will not go in much depth, but if you want to learn RMM in more depth, I recommend reading Richardson Maturity Model, steps toward the glory of REST written by Martin Fowler.

The RMM explains REST in four levels:

- Use a protocol to do remote procedure calls (RPC).

- Introduce Resources

- HTTP Verbs

- Hypermedia Controls

Let’s deconstruct all of these levels briefly.

Level 1 #

Level one basically states that we need to use a protocol (HTTP) to execute procedure calls on some remote location (a server). This also means that we will not use any of the mechanism that the protocol provides, but we will just use it as a tunnel to send the requests and responses.

Level 2 #

Level two is something very familiar to all of us, I am sure. Resources. Back in the day, when I was probably still in high school, RPC worked by communicating with a single endpoint on a server. This is called a “service endpoint”.

By implementing resources in an API, we provide multiple endpoints that will represent the resources. This means that instead of having one single multipurpose endpoint, we have an endpoint for every resource that the API exposes.

Level 3 #

With level 1 and level 2 the mechanisms of the protocol were skipped, because we think only about tunneling our calls instead of fully utilising the protocol. Level 3 takes this to the next level (pun intended) and states that any RESTful service needs to utilise HTTP verbs so clients can interact with resources.

If you are coming from Rails land, I am sure you already know this - there’s a big difference between GET, POST, PUT, PATCH and DELETE. Sure, you could handle these in various ways in your backend, but this is where Rails shines - it strongly encourages you to comply to REST.

If you do not obey Level 3 of the RMM, you could have a different endpoint for

every action on the API side. For example, if you had a Pet resource, to

create a new entry you could use a /pets/create or a /pets/update to update

it. By utilising Level 3, when HTTP verbs come into play, you would use

something that Rails makes super easy: GET /pets/:id to get a Pet, POST /pets to create a new Pet or PATCH /pets to update one.

Level 4 #

Now, while Rails does a great job to make you write RESTful APIs, Level 4 is something that falls onto you, the programmer, to implement. This is something that most of us don’t follow and we, as a community, still haven’t find the best way to accomplish.

Hypermedia Controls is REST’s “holy grail”, and the ultimate level of “RESTfulness”. It states that when an API is at level four, it’s clients can request resources in a specific data format and can navigate throughout the API by using Hypermedia Controls.

If you find this confusing, let’s take a step back and think about browsers and

websites. When you use a website you usually know only the entry point, in the

form of domainname.tld, like ieftimov.com or google.com. Then, by

interacting the website via your browser you navigate throughout the different

pages it has. Well, navigating is done by clicking on links, right? Imagine a

website that instead of having links makes your remember every URL on the

website and you have to type it in manually. Worst website ever!

Having this in mind, the idea of Hypermedia Controls means that a resource should provide links, so a client that consumes the resource can navigate through and interact with it without knowing any other endpoint except the entry point. Just like normal websites - the page provides you with the links so you can interact with it.

We will get into the format of the JSON responses that HATEOAS APIs return in a bit, but first we will look at another important mechanism of HATEAOS - content negotiation.

Content negotiation #

Content negotiation is a mechanism embedded into HTTP that allows web services

to serve different versions (or formats) of documents. Or in REST terminology,

resources. This is achieved by the Accept group of HTTP headers. For example,

when requesting a web page the user agent (the browser) sends these (or similar)

headers, depending on the browser:

Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/webp,*/*;q=0.8

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate, sdch, br

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.8This tells the server that the user agent can accept the document in a

text/html, compressed with one of the specified compression schemes, formatted

in en-US (US English) language.

If we go back to APIs, Rails does a very good job in content negotiation. When

we are building apps nowadays, we usually make sure our resources have a HTML,

JSON and (maybe) an XML representation. I am sure all of us have seen this:

respond_to :html, :json, :xml

def index

@pets = Pet.all

respond_with(@pets)

endOr maybe the older version of this code:

def index

@pets = Pet.all

respond_to do |format|

format.html

format.json { render :json => @pets }

format.xml { render :xml => @pets }

end

endThis tells our index action to allow three types of content format are

requested, via content negotiation. HTML, JSON and XML are in fact Media

(or MIME) types.

If you look at the example headers, you can notice the q parameter. This is

called a Quality Value and it is what makes one content type more important

than another. In other words, the q parameter adds a relative weight to the

preference for that associated kind of content.

For example, let’s say we have the following Accept header:

Accept: application/json; q=0.5, application/xml; q=0.001This tells the server that the client prefers JSON content type much more than

XML. If the q value is not specified, then the value is defaulted to 1. You

can read more about content negotiation in RFC 7231.

HATEOAS #

So what is HATEOAS? It is an acronym, just like REST, which translates to Hypermedia As The Engine Of Application State. Whoa, what a mouthful, right?

Like we mentioned, Level 4 of the RMM states that an API should provide hypermedia controls to navigate in and interact with. But, what does HATEOAS have to do with this? Well, think about this - REST means Representational State Transfer while HATEOAS means Hypermedia As The Engine Of Application State. If you look just as the names, it makes sense that HATEOAS is a mechanism of REST. It all revolves around application state and state transitions.

Too complex? Let’s see an example of a usual JSON representation of a resource, in this case, my user somewhere on a server:

curl http://awesomeapi.com/users/1{

"user": {

"first_name": "Ilija",

"last_name": "Eftimov",

"age": 25

}

}Simple enough. Now, when we apply HATEOAS to our representations of resources, it should look something like this:

{

"user": {

"first_name": "Ilija",

"last_name": "Eftimov",

"age": 25,

"links": [

{

"rel": "self",

"href": "http://awesomeapi.com/users/1"

},

{

"rel": "roles",

"href": "http://awesomeapi.com/users/1/roles"

}

]

}

}By providing the links we allow the clients to use hypermedia (in our case,

JSON) as the engine (list of available actions) of our application state

(changing the data on the API side). The idea here is that there should be only

one entry point to an API, or to a resource, and that the representation of the

resource should include all of the actions that can be executed on this

resources.

This means that a consumer of the API can take use the self attribute of the

User resource, and consider this the endpoint where it can execute actions on

it. By knowing that the API is RESTful, the client knows how to update the

resource:

curl -X "PUT" -d "{ 'age': 26 }" http://awesomeapi.com/users/1Also, it knows how to delete the resource:

curl -X "DELETE" http://awesomeapi.com/users/1Furthermore, if it wants to see all of the roles for this user, it can execute

a GET request to the roles relation of the user:

curl http://awesomeapi.com/users/1/rolesAs you can see, by putting HATEOAS in the mix, clients can interact with resources just by getting the URIs from the resources and by assuming that the API is level three RESTful (utilises HTTP verbs).

HATEOAS Serializers #

How can we make our Rails API implement Level 4 of RMM? Let’s see an example.

Our API is part of a blog CMS. It has an Author model, which has a

one-to-many association with an Article model. This means that, one Author

can have multiple Article.

The Author model:

# == Schema Information

#

# Table name: authors

#

# id :integer not null, primary key

# first_name :string

# last_name :string

# created_at :datetime not null

# updated_at :datetime not null

#

class Author < ApplicationRecord

has_many :articles

endAnd the Article model:

# == Schema Information

#

# Table name: articles

#

# id :integer not null, primary key

# author_id :integer

# title :string

# body :text

# created_at :datetime not null

# updated_at :datetime not null

#

class Article < ApplicationRecord

belongs_to :author

endOur routes look like the following:

Rails.application.routes.draw do

resources :authors do

resources :articles

end

endFinally, we will have serializers for both, the Article and the Author model.

For this example, we will use

Active Model Serializers.

Author serializer #

All of the Author objects will be serialized by the AuthorSerializer. Let’s

add the required attributes first to the serializer, and we can talk about

extension afterwards.

The AuthorSerializer class will look like this:

# == Schema Information

#

# Table name: authors

#

# id :integer not null, primary key

# first_name :string

# last_name :string

# created_at :datetime not null

# updated_at :datetime not null

#

class AuthorSerializer < ActiveModel::Serializer

attributes :id, :first_name, :last_name, :created_at, :updated_at

has_many :articles

type :author

endSuper simple! I will leave the annotations in, to keep the context of the data visible to us throughout this short example. In my everyday work, I usually consult with the schema file if I forget the shape of the data instead of adding annotations.

Let’s try sending a GET /authors request and see what the data looks like.

For reference, this is the implementation of the index action in the

AuthorsController:

class AuthorsController < ApplicationController

def index

render json: Author.all

end

endcurl http://localhost:3000/authorsThis request will return the following JSON:

[

{

"id": 1,

"first_name": "ilija",

"last_name": "eftimov",

"created_at": "2016-06-25T20:52:12.804Z",

"updated_at": "2016-06-25T20:52:12.804Z",

"articles": [

{

"id": 1,

"title": "Lorem ipsum",

"body": "Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet",

"created_at": "2016-06-25T22:25:51.874Z",

"updated_at": "2016-06-25T22:25:51.874Z"

},

{

"id": 2,

"title": "A princess of Mars",

"body": "His reference to the great games of which I had heard so much while among the Tharks convinced me that I had but jumped from purgatory into gehenna. After a few more words with the female, during which she assured him that I was now fully fit to travel, the jed ordered that we mount and ride after the main column. I was strapped securely to as wild and unmanageable a thoat as I had",

"created_at": "2016-06-26T00:20:09.388Z",

"updated_at": "2016-06-26T00:20:09.388Z"

}

]

}

]Since my database has only one Author instance, it returns only that one.

Also, the Author has two associated Article instances, so the serializer

includes them in the response.

Adding links to our serializer #

Now we have our serializer working. The next step is to extend it with links.

This is quite trivial to do using Active Model Serializers - we need to add a

new links attribute to the serializer, and provide the implementation of the

attribute (which will be a method in fact) in the class:

# == Schema Information

#

# Table name: authors

#

# id :integer not null, primary key

# first_name :string

# last_name :string

# created_at :datetime not null

# updated_at :datetime not null

#

class AuthorSerializer < BaseSerializer

attributes :id, :first_name, :last_name, :created_at, :updated_at, :links

has_many :articles

type :author

def links

[

{

rel: :self,

href: author_path(object)

}

]

end

endAs you can see, the implementation is quite simple. We add a new attribute

called links, and the method just returns an array of hashes. For starters,

we will have only one - the self link which will point to the resource whose

representation we are seeing.

But, if you execute the curl request again, you will gen an error, something like:

#<NoMethodError: undefined method `author_path' for #<AuthorSerializer:0x007fe251b4c450>>This occurs because Rails’ route helpers are not included in the scope of the serializers. This is easily fixable by including them to the serializer:

class AuthorSerializer < ActiveModel::Serializer

include Rails.application.routes.url_helpers

# *snip*

endIf we execute the curl request again now, we will see the links in the JSON:

[

{

"id": 1,

"first_name": "ilija",

"last_name": "eftimov",

"created_at": "2016-06-25T20:52:12.804Z",

"updated_at": "2016-06-25T20:52:12.804Z",

"links": [

{

"rel": "self",

"href": "/authors/1"

}

],

"articles": [

{

"id": 1,

"title": "Lorem ipsum",

"body": "Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet",

"created_at": "2016-06-25T22:25:51.874Z",

"updated_at": "2016-06-25T22:25:51.874Z"

},

{

"id": 2,

"title": "A princess of Mars",

"body": "His reference to the great games of which I had heard so much while among the Tharks convinced me that I had but jumped from purgatory into gehenna. After a few more words with the female, during which she assured him that I was now fully fit to travel, the jed ordered that we mount and ride after the main column. I was strapped securely to as wild and unmanageable a thoat as I had",

"created_at": "2016-06-26T00:20:09.388Z",

"updated_at": "2016-06-26T00:20:09.388Z"

}

]

}

]Great stuff! We added some HATEOAS to our resources.

Specifications #

Before we continue to add any more hypermedia to our resources, we need to put

some thought into this. As you can see, we went on to implement the links

attribute to the serializer without any thought. Sure, you might say, I am the

creator of the API and I will structure the responses of the API as I please.

True, you are the author of the API, but that statement is false. Imagine if all of us thought of a way to implement hypermedia in a different way? Every single API would be different in it’s hypermedia controls and it would be a hell to find your way around.

Well, the sad part is that we still don’t know how to do HATEOAS. Or better said, we still don’t know the best way to do HATEOAS. That is why, people have tried to create specifications, which have been somewhat adopted.

HAL #

From HAL’s documentation:

HAL is a simple format that gives a consistent and easy way to hyperlink between resources in your API.

As you can see, the motivation behind HAL is to create an easy and consistent way to add hypermedia controls. Just like any other specification, HAL provides a set of conventions for expressing hyperlinks in either JSON or XML.

This is an example of a JSON that applies the HAL specification:

{

"_links": {

"self": { "href": "/orders" },

"curies": [{ "name": "ea", "href": "http://example.com/docs/rels/{rel}", "templated": true }],

"next": { "href": "/orders?page=2" },

"ea:find": {

"href": "/orders{?id}",

"templated": true

},

"ea:admin": [{

"href": "/admins/2",

"title": "Fred"

}, {

"href": "/admins/5",

"title": "Kate"

}]

},

"currentlyProcessing": 14,

"shippedToday": 20,

"_embedded": {

"ea:order": [{

"_links": {

"self": { "href": "/orders/123" },

"ea:basket": { "href": "/baskets/98712" },

"ea:customer": { "href": "/customers/7809" }

},

"total": 30.00,

"currency": "USD",

"status": "shipped"

}, {

"_links": {

"self": { "href": "/orders/124" },

"ea:basket": { "href": "/baskets/97213" },

"ea:customer": { "href": "/customers/12369" }

},

"total": 20.00,

"currency": "USD",

"status": "processing"

}]

}

}JSON API #

JSON API, just like HAL is:

a specification for how a client should request that resources be fetched or modified, and how a server should respond to those requests.

It was was originally drafted by Yehuda Katz in 2013. This first draft was extracted from the JSON transport implicitly defined by Ember Data’s REST adapter. From there on, it picked up some popularity, but I cannot say with certainty that it’s the de facto API specification.

This is an example of a JSON that applies the JSON API specification:

{

"data": [{

"type": "articles",

"id": "1",

"attributes": {

"title": "JSON API paints my bikeshed!",

"body": "The shortest article. Ever.",

"created": "2015-05-22T14:56:29.000Z",

"updated": "2015-05-22T14:56:28.000Z"

},

"relationships": {

"author": {

"data": {"id": "42", "type": "people"}

}

}

}],

"included": [

{

"type": "people",

"id": "42",

"attributes": {

"name": "John",

"age": 80,

"gender": "male"

}

}

]

}Other standards #

As you can imagine, people have tried to create a good JSON standard for quite some time. Some of the more popular specs are JSON for Linking Data, also known as JSON-LD; Collection+JSON and SIREN.

JSON API and Active Model Serializers #

Since JSON API is picking up momentum and Active Model Serializers has a very good integration of it, we will stick to it and carry on with the implementation. Active Model Serializers on a high-level works through two parts: serializers and adapters. From the documentation:

Serializers describe which attributes and relationships should be serialized. Adapters describe how attributes and relationships should be serialized.

To get our JSON serialized in the JSON API format, we need to use a different

adapter called, believe it or not, :json_api. Personally, I prefer to do this

type of configuration in an initializer file:

# config/initializers/active_model_serializers.rb

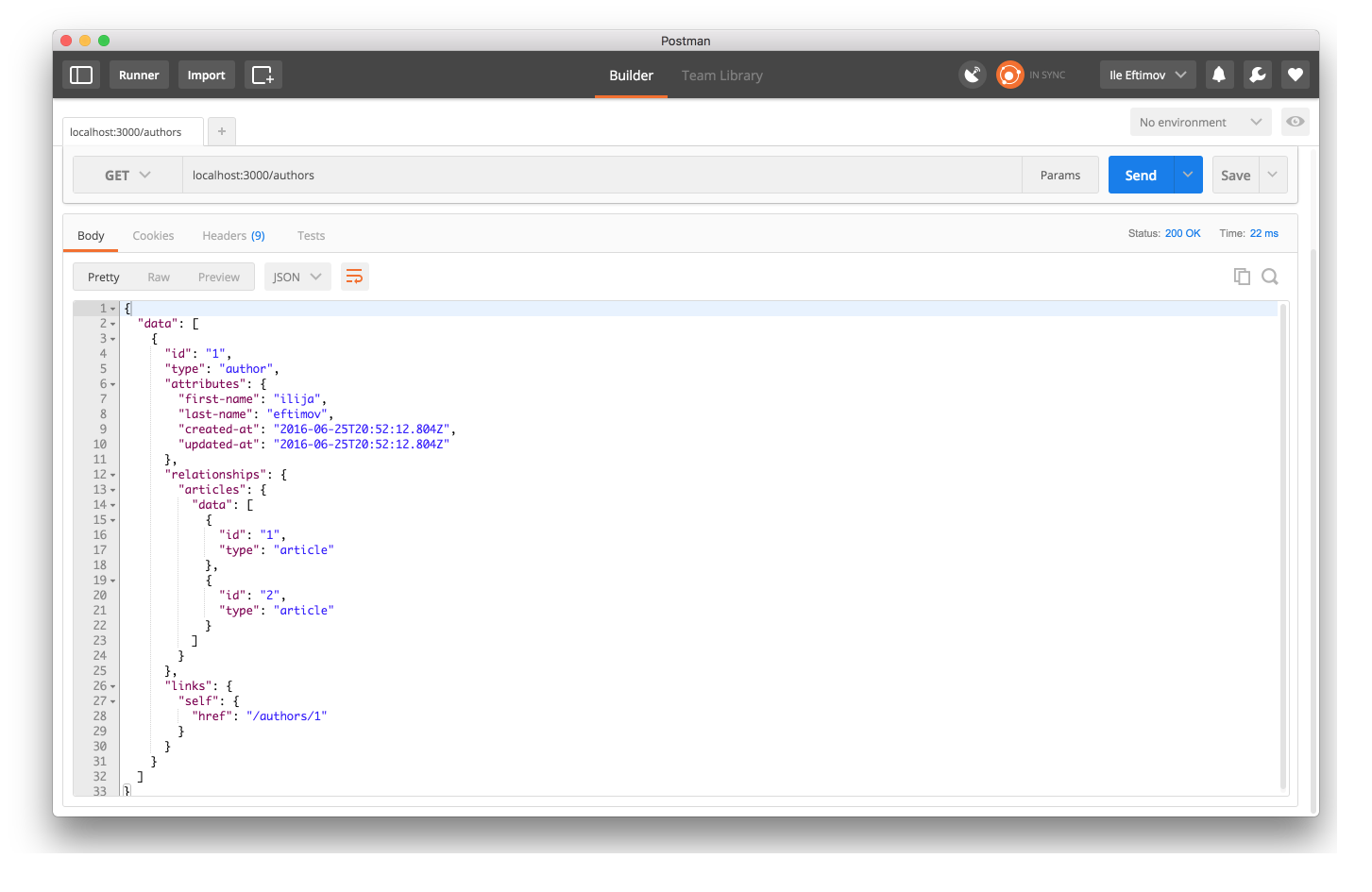

ActiveModelSerializers.config.adapter = :json_apiBy setting the adapter to :json_api, our API will produce and consume JSON

formatted in the JSON API spec. If we execute the same API call that we did

earlier, we will get a newly formatted JSON:

{

"data": [

{

"id": "1",

"type": "author",

"attributes": {

"first-name": "ilija",

"last-name": "eftimov",

"created-at": "2016-06-25T20:52:12.804Z",

"updated-at": "2016-06-25T20:52:12.804Z"

},

"relationships": {

"articles": {

"data": [

{

"id": "1",

"type": "article"

},

{

"id": "2",

"type": "article"

}

]

}

},

"links": {

"self": {

"href": "/authors/1"

}

}

}

]

}As you can notice, the JSON that we get back has a completely different structure compared to what we have before. The reason is that the JSON API adapter that we use now formats the JSON in the JSON API Spec format.

Another cool thing about the JSON API adapter is that it allows us to specify links very explicitly, with a very nice DSL:

class AuthorSerializer < ActiveModel::Serializer

attributes :id, :first_name, :last_name, :created_at, :updated_at

has_many :articles

type :author

link :self do

href author_path(object)

end

endAlso, we do not have to specify the links as an attribute and we can remove

the include line that mixed-in Rails’ url helpers in our serializer. If we

call the /authors endpoint with a GET request again, we will see an

extended JSON, that again complies with the JSON API Spec:

{

"data": [

{

"id": "1",

"type": "author",

"attributes": {

"first-name": "ilija",

"last-name": "eftimov",

"created-at": "2016-06-25T20:52:12.804Z",

"updated-at": "2016-06-25T20:52:12.804Z"

},

"relationships": {

"articles": {

"data": [

{

"id": "1",

"type": "article"

},

{

"id": "2",

"type": "article"

}

]

}

},

"links": {

"self": {

"href": "/authors/1"

}

}

}

]

}Including additional resources #

Since AMS is an awesome gem, it allows you to include additional resources by including them in the controllers:

class AuthorsController < ApplicationController

def index

render json: Author.all, include: 'articles'

end

endBy including the Article association of on the Author model, we are able to

extend the JSON result with the associated articles for each of the users:

{

"data": [

{

"id": "1",

"type": "author",

"attributes": {

"first-name": "ilija",

"last-name": "eftimov",

"created-at": "2016-06-25T20:52:12.804Z",

"updated-at": "2016-06-25T20:52:12.804Z"

},

"relationships": {

"articles": {

"data": [

{

"id": "1",

"type": "article"

},

{

"id": "2",

"type": "article"

}

]

}

},

"links": {

"self": {

"href": "/authors/1"

}

}

}

],

"included": [

{

"id": "1",

"type": "article",

"attributes": {

"title": "Lorem ipsum",

"body": "Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet",

"created-at": "2016-06-25T22:25:51.874Z",

"updated-at": "2016-06-25T22:25:51.874Z"

},

"relationships": {

"author": {

"data": {

"id": "1",

"type": "author"

}

}

},

"links": {

"self": {

"href": "/authors/1/articles/1"

}

}

},

{

"id": "2",

"type": "article",

"attributes": {

"title": "A princess of Mars",

"body": "His reference to the great games of which I had heard so much while among the Tharks convinced me that I had but jumped from purgatory into gehenna. After a few more words with the female, during which she assured him that I was now fully fit to travel, the jed ordered that we mount and ride after the main column. I was strapped securely to as wild and unmanageable a thoat as I had",

"created-at": "2016-06-26T00:20:09.388Z",

"updated-at": "2016-06-26T00:20:09.388Z"

},

"relationships": {

"author": {

"data": {

"id": "1",

"type": "author"

}

}

},

"links": {

"self": {

"href": "/authors/1/articles/2"

}

}

}

]

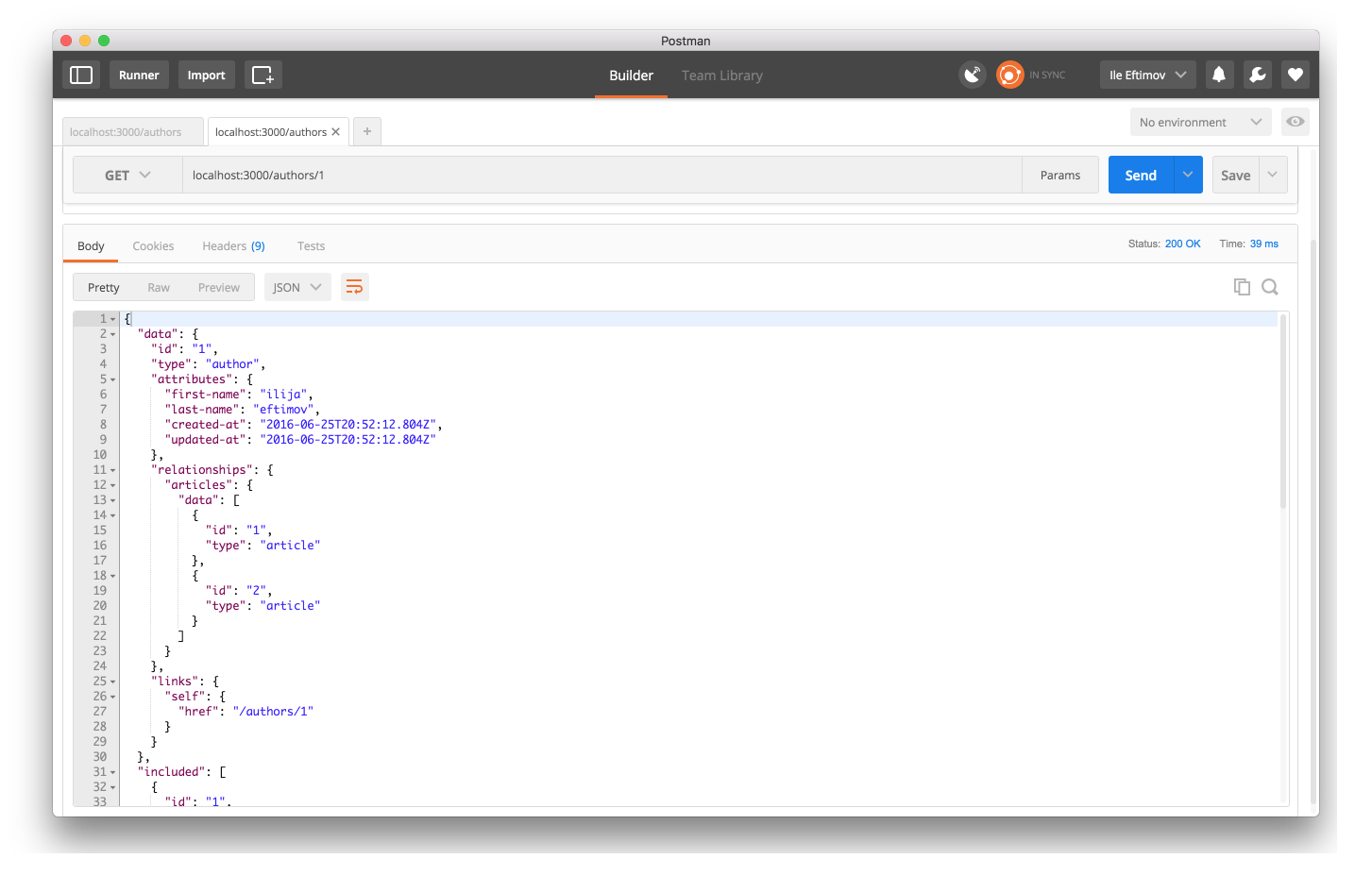

}Although this is quite nice, beware that this introduces N+1 queries for every

resource that we fetch. That’s why, usually index actions return only the

requested resources, while show actions tend to include some additional

resources:

class AuthorsController < ApplicationController

def index

render json: Author.all

end

def show

author = Author.find(params[:id])

render json: author, include: :articles

end

endThis will add all of the articles found for the author that we requested:

{

"data": {

"id": "1",

"type": "author",

"attributes": {

"first-name": "ilija",

"last-name": "eftimov",

"created-at": "2016-06-25T20:52:12.804Z",

"updated-at": "2016-06-25T20:52:12.804Z"

},

"relationships": {

"articles": {

"data": [

{

"id": "1",

"type": "article"

},

{

"id": "2",

"type": "article"

}

]

}

},

"links": {

"self": {

"href": "/authors/1"

}

}

},

"included": [

{

"id": "1",

"type": "article",

"attributes": {

"title": "Lorem ipsum",

"body": "Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet",

"created-at": "2016-06-25T22:25:51.874Z",

"updated-at": "2016-06-25T22:25:51.874Z"

},

"relationships": {

"author": {

"data": {

"id": "1",

"type": "author"

}

}

},

"links": {

"self": {

"href": "/authors/1/articles/1"

}

}

},

{

"id": "2",

"type": "article",

"attributes": {

"title": "A princess of Mars",

"body": "His reference to the great games of which I had heard so much while among the Tharks convinced me that I had but jumped from purgatory into gehenna. After a few more words with the female, during which she assured him that I was now fully fit to travel, the jed ordered that we mount and ride after the main column. I was strapped securely to as wild and unmanageable a thoat as I had",

"created-at": "2016-06-26T00:20:09.388Z",

"updated-at": "2016-06-26T00:20:09.388Z"

},

"relationships": {

"author": {

"data": {

"id": "1",

"type": "author"

}

}

},

"links": {

"self": {

"href": "/authors/1/articles/2"

}

}

}

]

}As you can notice, because we supplied the has_many association in the

serializer, AMS knows to utilise the correct serializer for each of the

included resources. This adds the same structure to the included resources and

the requested resource, which makes the result consistent and parsing this JSON

much easier.

Navigating resources #

Now, to actually see how easy it is to navigate through resources, let’s

implement the ArticlesController#show action as well:

class ArticlesController < ApplicationController

def show

article = Article.find_by(author_id: params[:author_id], id: params[:id])

render json: article

end

endSuper simple - we find the Article by the author_id and the id params and

render it as a JSON. If we call GET /authors/1/articles/2, we will get the

JSON API representation of the Article object:

{

"data": {

"id": "2",

"type": "article",

"attributes": {

"title": "A princess of Mars",

"body": "His reference to the great games of which I had heard so much while among the Tharks convinced me that I had but jumped from purgatory into gehenna. After a few more words with the female, during which she assured him that I was now fully fit to travel, the jed ordered that we mount and ride after the main column. I was strapped securely to as wild and unmanageable a thoat as I had",

"created-at": "2016-06-26T00:20:09.388Z",

"updated-at": "2016-06-26T00:20:09.388Z"

},

"relationships": {

"author": {

"data": {

"id": "1",

"type": "author"

}

}

},

"links": {

"self": {

"href": "/authors/1/articles/2"

}

}

}

}If you use Postman, which I really enjoy using, or any other API browser to test the endpoints you could see how easy it is to navigate the resources:

Just link in the web browser, you know the entry point

localhost:3000/authors. From there you can click on the links property of

the Author and get the single Author resource:

By seeing the resource with all of it’s included resources, then you can click

on any of the links on the included Article resources, and see their

attributes in JSON format:

This is what essentially HATEOAS means - navigating and interacting with resources via the endpoints that are provided in the JSON representation of the resources.

Outro #

As you can see, to understand and learn what Hypermedia As The Engine Of Application State is, there is quite a bit of context that we need to get in our heads. Although all of this sometimes can appear as quite complex, Rails makes implementing HATEOAS APIs quite easy, as you could see in the examples. Sure, there is more to hypermedia controls, but these examples should be more than enough to get your feet wet.

Also, the HATEOAS concept seems quite complex on the surface, but when you deconstruct it it’s quite simple, because we have already seen the same behaviour in web browsers. The issue of why it seems quite complex is because we haven’t even thought about normal web sites like RESTful APIs, and vice-versa.

If you want to see the actual implementation of the endpoints that we worked with in this article, you can check this repo on Github.